The Fig Tree - Issue 7

with Featured Poet Bob Horne

Welcome to the seventh issue of The Fig Tree, and its a special one not only because it's our first anniversary but also because we have taken the opportunity to pay a small tribute to a man who has played an important role in supporting poetry in Yorkshire over the past decade through the conduit he has provided in creating his Calder Valley Poetry press and in publishing so many fabulous poets. Bob is winding down his CVP activities in 2025 so I have asked one of the poets he published, Ian Parks, to provide some words about Bob that explain what he has meant to the people he has worked with.

Partially in response to Bob’s decision to wind down CVP, and the loss of the formidable northern publisher Smokestack, I have decided to start my own publishing venture. The first book of Crooked Spire Press will be an anthology of poems from the 2024 issues of The Fig Tree - this is now at an advanced stage and will be available soon.

In addition to the regular issues, 2025 will see the first Fig Tree Special Issue on the theme of Coal Mining – miners, the 1984-1985 strike in the UK and the communities before, during and after the strike. Submissions continue to be open until April 30th but we have already had a lot of quality submissions and I will be publishing in two parts, one in March and another in June. It may be that I have to close submissions early so don't hesitate to get your poems in!

Once again I hope you enjoy reading this issue as much as I did collating it. You are joining over 500 people who are reading the webzine on a regular basis.

Thank you all

Tim Fellows, Editor

Contributors: Bob Horne, Ian Parks, Michael Burton, Eleanor Cantor, Stewart Carswell, Becky Deans, Craig Dobson, Oz Hardwick, Sarah James, Matthew Paul, Eileen Thompson, Rodney Wood and Paul Brough.

The Fig Tree Featured Poet – Bob Horne

Before we look at Bob's work, here is the promised piece by Ian Parks about Bob, Calder Valley Poetry and his own poetry.

Bob Horne is widely regarded as a gifted and sensitive editor. His Calder Valley Poetry has gone from strength to strength over the last decade, building a staple of first-rate contemporary poets that most publishing houses could only hope to emulate. The quality and integrity of the enterprise is entirely due to the instincts and dedication of the editor himself and the calibre of the poets he chooses to publish. At a time when mainstream poetry is suffering a serious recession, Calder Valley Poetry is burning a conspicuous torch. Most of the success of the press, I’d argue, comes from the fact that the editor is also a very fine poet in his own right too – a poet with a rare sensibility and an ear fully attuned to the nuances and possibilities of language. Most of Bob’s poems (the ones, that is, he wants us to know about) are collected in Knowing My Place which was published by Caterpillar Poetry in 2017. Although the poems are separate, free-standing pieces, the insistence on memory and place invites a reading of them as a sequence. Bob Horne has inherited Hardy’s insights into the inseparability of time and place in memory and creates out of it a poetry of depth and resonance. The title of the collection itself invites two tantalising interpretations: that the poet is possessed of a thorough knowledge and love of the places he chooses to write about and, in another sense, that he remains modest about the achievement. The location of these places are invariably the Lake District and the Yorkshire Dales where the distinctive characteristics of the landscape act not so much as backdrops to the events (often internal ones) but as an objective correlative for the emotional states they instil. In Ancestry, for instance, Horne responds to the past not through his own memories but through the memories of his parents, their cycling through the countryside and returning ‘home for tea’. In No Matter the poet describes cycling through a flock of sheep. And in The Cricketers at Keswick (cricket is an abiding passion) he connects the present and the past deftly and with compelling understatement:

Norsemen came here, cleared the land of rocks

the last Ice Age left behind

so cattle could be kept, cricket can be played.

The voice is distinctive for all its quietness; it is distinctive because of its quietness. Behind Bob Horne’s modesty and reticence, we are invited to hear and identify with the modesty and reticence of Hardy and of Edward Thomas too, a poet who connected at a fundamental level with the English landscape. Before doing us all a great service by becoming an editor Bob Horne worked variously as a much-loved and respected English teacher, a milkman, and a stone worker. It’s very good to see his impressive work featured in The Fig Tree.

Ian Parks

The Last Bus

That autumn you always missed it

so I would walk with you along unlit lanes

even though, for me, it was miles

in the wrong direction.

One night, still and starless, halfway

to where you lived, we stopped,

leant on a wall, woodland tumbling

to a beck in the bottom.

Across the valley sprinklings of light

spread over moorland blackness.

We stared ahead into the dark

until a scattering of raindrops

on the leaves beneath us,

a haphazard pattering

that never became a downpour,

was enough to hurry us forward.

And that was all, though I wonder

do you still have the poem I wrote

for your eighteenth birthday?

The copy of Blonde on Blonde

you kept promising to return

next time we met?

Bob Horne

Neighbour

(i.m. Tony Wilson)

After the war he bred pigs

in the crumbling outbuildings of Crow Nest mansion

where unexpected crashings would shake

the silence of still summer nights

as three-hundred-million-year-old millstone grit

settled back into the grass.

Once, he was a black-haired horseman

with an Errol Flynn moustache,

three-quarter in the rugby team,

hands in pockets in that focussed moment,

imagining, I imagine,

this will last for ever.

In the Burma jungle, late one afternoon,

while he lolled with a cigarette

beside a mound of foreign flowers

by a single track railway,

an air attack reduced his platoon to one.

He came home, horse bolted,

sweethearts metamorphosed and married,

not knowing his own mother.

When I helped for a day

we picked up feed at the flour mill,

filled the troughs with swill,

marvelled at the massive old boar

rising from the straw

like a great whale outgrowing its ocean,

bristles like a brush’s on its back.

After thirty years he put on his coat,

let himself out, walked down the grounds,

scratched his hands on the brambles

as he climbed the embankment

and lay on the Ilkley line

in front of the evening train,

having, the papers said,

been depressed for some time.

Bob Horne

Churchyard

I go among headstones, last summer's leaves, in a new year, opaque and cold. Time of winter waiting. From close cover a wren blurs the edge of vision, lights an instant on a fallen cross, cock- tailed and querulous. Two fields away the cricket pavilion is an anachronism, clock stopped at September. Here are carved words for the wordless, not gone but growing. The coexistent dead, seasoned, lasting again into lengthening days. In the mornings the unnamed rose to toil in the grey fields. They loved, and mourned the loss of those they loved, felt the cold coming over the knoll, lolled on drystone walls, warm in the summer sun, another day done. No pew in the church, no servants or nurse, no chiselled dates, no words to tell the years to come they were better than they'd been. Beasts in the fields their epitath, ground ploughed over and over, sowing and harvesting, sweat of summer, numb of winter. Low sun over Birkby Hill splinters through bare branches of oak and beech and thorn, scatters across remembrances of the long-lived, of infant mortality, the pure of heart, sung to their rest by flights of angels. The lover and the loved.

Bob Horne

Bob Horne has been writing poems on and off, mostly off, since the 1960s. Thirty years ago he completed an MA in poetry at Huddersfield University. In 2016 he set up Calder Valley Poetry, and has since published 35 collections and pamphlets. In 2017 his own collection, ‘Knowing My Place’, was published by Caterpillar Poetry. With John Foggin he ran Puzzle Hall Poets from 2014 to 2020. He once hooked a West Indies Test fast bowler for six.

The Fig Tree Selection – March 2025

This section features up to ten poems, with a maximum of one per poet per issue.

Medusa

alone in her bungalow, eyes the rising sun.

A shingle of flies pricks each carpeted step.

Lizards that stole in from the unkempt garden

ornament unendingly. Creeping through cobwebs

torn by petrified spinners, dawn warms the drawn

curtains that couldn’t hide her cold assassins.

Silence hisses. Staring at the fears between each stillness,

she’s blinded by the flowers she caresses – doing her best

with leaf and stem to remember fur and feather, the god-gift of skin.

But, following the sun, each bloom leaves her

to the worn patterns in the kitchen lino and the dust

gathering on the furniture and on each hero’s stony shoulder,

and to the memories her beauty once moved

and a future that won’t see past the love reflected in its eyes.

Craig Dobson

My Own Good Samaritan

Each morning, my reflection in shop windows recedes a little further, my face tilting away from the lights as it avoids my eyes. My analyst tells me to make friends with the slow loss, and that such occurrences are perfectly normal. I’m at that age at which every day brims with epiphanies and grand revelations, but each time she says normal, I weep like a pilgrim who has crawled for miles on hands and knees to kiss the ragged hem of the sacred. This, she tells me, resting her index finger lightly on my forehead, is also normal. And so, in the evening, when those same windows fill with nothing but sunset, blazing like consecrated wine, the only reflection I see is my analyst, stamping out a cigarette with her bare feet as she opens her car door. It is dark for this time of year. It is always dark. It is always this time of year. There is someone in the passenger seat who appears to be laughing or crying, though it’s hard to tell which, as they’re wearing a mask that’s crudely cut from the face I used to wear when I could still look myself in the eye.

Oz Hardwick

Biyela Lodge to Cape Town

We wave goodbye to impalas—hindquarters flashing

like punctuation through bone-dry brush,

each marked with an unexpected McDonald's arch:

wild bodies writing in dust and muscle.

The road to the airport: a landscape of fracture,

potholes gaping like wounds in the earth's skin,

deep enough to swallow entire migrations,

entire histories of movement and survival.

Beside homes, small huts whisper to ancestral ghosts,

keeping memory warm, keeping silence closer than breath.

The world tilts: girls balancing water, gravity's dancers,

their steps a choreography of necessary endurance.

Commuters stage exhaustion's bare performance,

each face a landscape of unspoken narratives,

waiting rooms where dreams and survival intersect.

This continent: a patchwork of dream and dirt,

where wilderness meets human geography.

That tortoise for example—grandfather-clock slow—

vanishing into brush, a meditation on persistence.

In Cape Town, our floating palace pauses:

Michaela Strachan speaks of penguins,

tuxedoed mourners on shrinking shores,

their black and white formality a quiet resistance

against climate's slow, relentless erasure.

Inside, guests strut, exotic birds wearing silk

and satin, eyes waiting for camera's brief coronation,

strutting between polished forks and practised smiles.

But the penguins know something deeper:

a dignity beyond spectacle, beyond survival—

a quiet rebellion against disappearance,

their dinner jackets a last, elegant protest

against the world's relentless erasure.

Rodney Wood

The Other Side of the Moon

Rock hard, the moon holds its secrets

closer than the night sky, tighter than

the brightest constellations

and for longer than the human eye.

Back to us, like my grandfather,

all we’re shown is one side: pure moon,

pure man in silhouette. The rest

could be starlit, could be shadow.

Nothing has ever happened there.

At least, not as far as our day knows,

or folks see, even with telescopes

sharper than my gran’s gaze –

all we get is an opaline outline.

Sarah James

Not Strictly

The mini tornados

Used their elbows

To get to the judges.

Chest out.

They were nine years old.

They went to glamorous

Places like

Coalville Town Hall and

Drayton Manor Park

And stomped.

They knew how to strike a pose.

The mini tornados

Wore leotards

Or costumes someone’s mum

Or momar had made

Of sequins and lacquer

High cheekbones

Hair slicked back

And rainbows.

Were the skirts too short?

I can never remember.

Becky Deans

Søren

Holding court

Half king half clown

As they crudely fill my glass

As the men all laugh and nod

At allusions which I know are beyond their grasp

As the hostess cannot help

But turn her head from guest to guest

In what she deems a secret smile

Her eyes proclaim:

Isn’t he all I have promised you and more?

God! Why have you forsaken me?

Why have you not killed me young?

Why have you let me live and be

Fifty-five

A bachelor

In this place

And with these people to whose loveless

Fascination with me I am bound?

I plead the late hour and they set me free.

When I get up from this here chair

In this here café

My walk is purgatory

Between two hells:

My hackneyed and applauded epigramming caricature

And my solitary flat.

I leave them young and rich

Or rich to be

They watch me stagger to the exit

I add a drunken limp

Or bump into a chair

For more effect

For those who bought my drinks.

There go I – the kept poet.

Think no more of me.

Return to your flirtations.

An entertaining time was had by all.

Eleanor Cantor

Nostalgia

The fallen tree with its collapsed crown

blocks the path like a ragged rake

so each time now when I’m walking back

I stop to pick my way through the boughs

pretending I’m 10ft up in air

and climbing trees again, ascending as a child

to where my vision is limited

to this old, decayed, deciduous.

Stewart Carswell

Boys will be Boys

It’s strange how memories still can sting and bite:

I smell the aroma of spuds and sausages burning,

see smoke twisting upwards in tendrils of flickering light,

rising from campfires where the spits are turning.

I taste charred skin in my starved imagination;

my mouth is watering, my stomach churning.

In thrall to this teasing olfactory temptation,

I hover in the shadows in the margins of the wood –

a silent, yearning bundle of gustatory frustration.

If only I’d been born a boy I could

have been a party to such camaraderie,

played Baden Powell searching for firewood,

enjoyed male bonding and the bonhomie

which typifies these gatherings and their like.

I would feel happy and fulfilled and free

if burning sausages were all the world could ask of me.

Eileen Thompson

Comedians’ Comedian

They all laughed when I said I’d become a comedian. Well, they’re not laughing now.

- Bob Monkhouse

Graham Henderson letrasets a comic called Pugwash

and flogs it to gullible first-years, like me. Awash

with gags, good ones at that, all his own material,

it instantly attains cult status. After school,

‘Gray’ plays the Last of the Summer Wine theme-tune

on harmonica, with extra-mournful lamentation,

as befits the sight of another full 213 trolling

along London Road without stopping.

*

Late-Eighties, he bags a first as insurance,

in International Banking and Finance,

changes his name to ‘Brucie Tarbuck’

and bins his specs, to work

the comedy circuit hard. Twice I catch

his proto-post-postmodern act:

both times, the not-really-jokes wash

over my head with a whoosh.

Matthew Paul

The Fisherman’s Foe

I spotted once a fisherman shortly after sunrise,

his feet welly-deep in the grotty reeds

on the bank across from me.

I watched him creep through the dark green water,

tracked the speed of his strides, the pitches

of plastic squeaks from his grime-stained waders.

He stopped at times to listen or squinted

in search of scales beneath the thick froths and slime.

When his prey arrived we both caught sight of her,

sharpened our stares, slowly lowered the knees.

A stone dug from the grass now tight within my hand,

poised, for when the time was right to set her free.

Michael Burton

Contributors

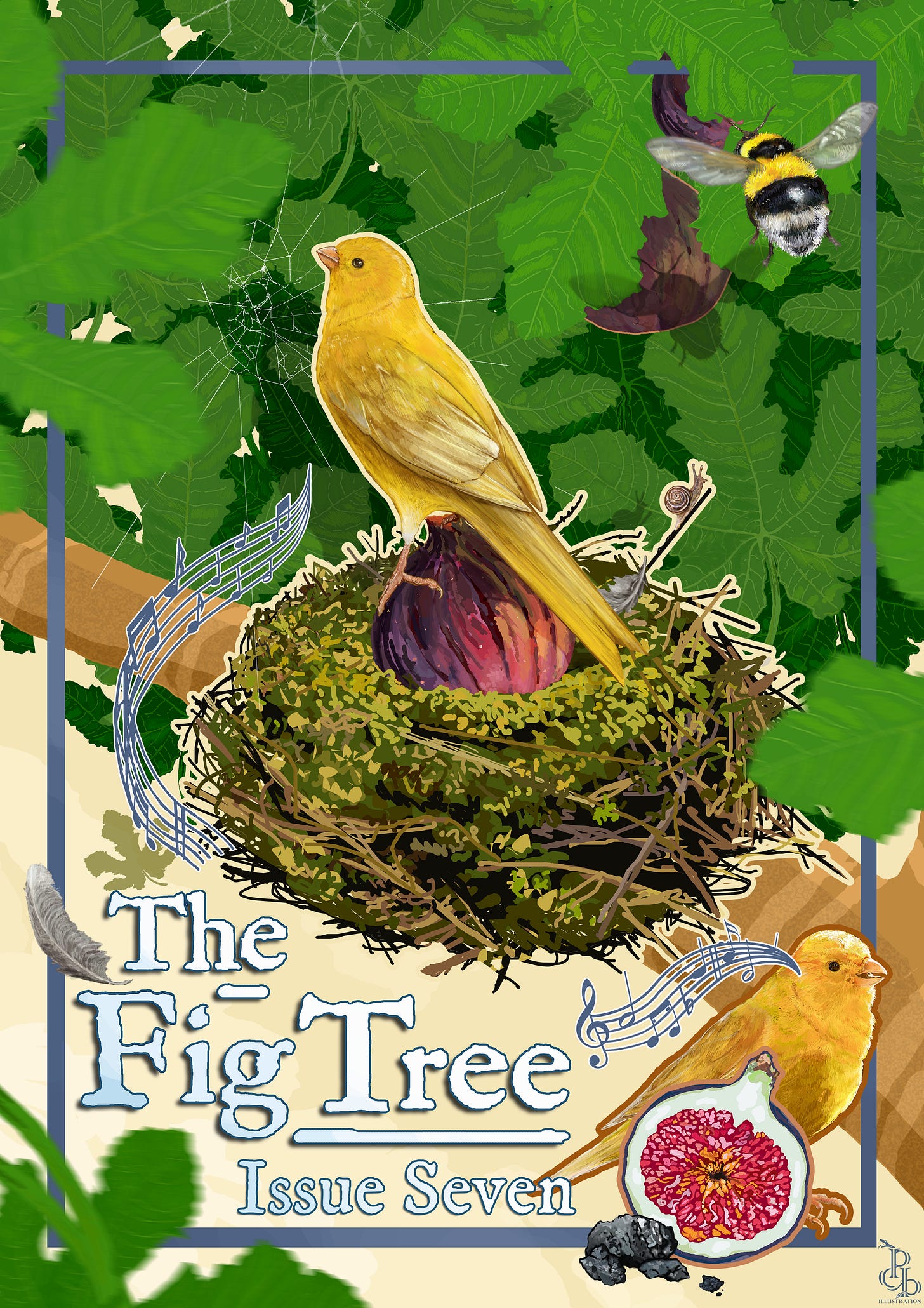

Paul Brough is a Yorkshire based illustrator. You can see more of his artwork here

Michael Burton’s poems have been published most recently in The Interpreter’s House, The Honest Ulsterman & Pennine Platform. He also writes and performs as NotAnotherPoet and is one half of the band New Age of Decay whose debut album can be found on various online streaming platforms.

Eleanor Cantor is a writer, translator and musical performer based in Yorkshire. Her work appeared in Poetry Quarterly, Wingless Dreamer, In Parentheses, Klecksograph, Free-the-Verse, Plate of Pandemic, WAPoets and elsewhere. She is the 2024 winner of the Ellie J Shakerley Poetry Award. Her music can be found at www.sisterchainbrotherjohn.com

Stewart Carswell grew up in the Forest of Dean and currently lives in Cambridgeshire, where he co-hosts the Fen Speak open mic night. His poems have recently been published in Under the Radar, Finished Creatures, Ink Sweat & Tears, and The Storms Journal. His debut collection is "Earthworks" (Indigo Dreams, 2021). Find out more at www.stewartcarswell.co.uk

Becky Deans is a poet, carer, copywriter, and clarinet teacher, who has curated and hosted spoken word events at local arts festivals including Belper Goes Green and Duffield Arts Festival. Her first novella was published in 1998 and her poetry chapbook, un(in)formed, was published by Bearded Badger Publishing in April 2021.

Craig Dobson has had poems and short fiction published in various UK, US and European magazines. He’s working towards his first book of poetry.

Oz Hardwick is an international award-winning prose poet, who has published “a dozen or so” full collections and chapbooks, most recently Retrofuturism for the Dispossessed (Hedgehog, 2024). He has also edited several anthologies, most recently Dancing About Architecture and Other Ekphrastic Maneuvers (MadHat, 2024) with Cassandra Atherton.

Sarah Leavesley/James is a prize-winning poet, fiction writer, journalist and photographer. Her recent collection Blood Sugar, Sex, Magic (Verve Poetry Press) won the CP Aware Award Prize for Poetry 2021 and was highly commended in the Forward Prizes. She also runs V. Press, publishing poetry and flash fiction. Website: http://sarah-james.co.uk

Ian Parks is the editor of Versions of the North: Contemporary Yorkshire Poetry. His versions of the modern Greek poet Constantine Cavafy were a Poetry Book Society Choice. His Selected Poems 1983-2023 is published by Calder Valley Poetry. His work appears in the Folio Book of Love Poems.

Matthew Paul was born and grew up in South London and now lives in South Yorkshire. His collection, The Evening Entertainment, was published by Eyewear in 2017. He is also the author of two haiku collections, published by Snapshot Press. He writes reviews and essays and blogs about poetry, here.

Eileen Thompson is a retired teacher and ex-patriot Geordie living in East Yorkshire with her husband and two greyhounds. She reads and writes poetry in an attempt to make sense of the world and consumes large amounts of genre fiction in order to escape from it.

Rodney Wood worked in London and Guildford. His poems have appeared recently in The High Window, The Pomegranate (London), Black Nore Review and Seventh Quarry. His debut pamphlet, Dante Called You Beatrice, appeared in 2017. He is MC of a monthly open mic night in Woking.

All contributors retain copyright of their work.

Love the range of this selection.

What a lovely constellation of poems 😀